When you walk into class on a Monday morning, it’s likely the projector is on and instructions are posted on a Smart Board. The teacher, at some point, will incorporate the use of the Chromebook into the lesson. The textbook has a digital version; homework is submitted online, and this cycle repeats for nearly every class.

Since the technology was introduced to education, learning has changed dramatically. We scrapped chalkboards for whiteboards, ditched computer screens for touch screens, and so on. Technology can be a beneficial tool in the classroom, but the advancements bring unexpected consequences.

Required online district programs, state testing, and Google Classroom school work, is it too much technology? What school work is better done the traditional way? Is this new way of learning actually benefiting students? What is the future of traditional learning?

When should screens be used and what effect do they have?

Some ages should be using more technology than others. Children don’t need to be staring at a screen to learn the alphabet, but older kids might need a computer to write a paper.

The subject matter has to be taken into consideration. If students are learning how to code, it makes sense that they’ll need to use some kind of digital device. On the other hand, students reading books don’t need to be looking at an online copy of a novel.

Common Sense Education states, ”It’s essential to think about whether digital media and technology are enhancing students’ learning, or potentially even detracting from it.”

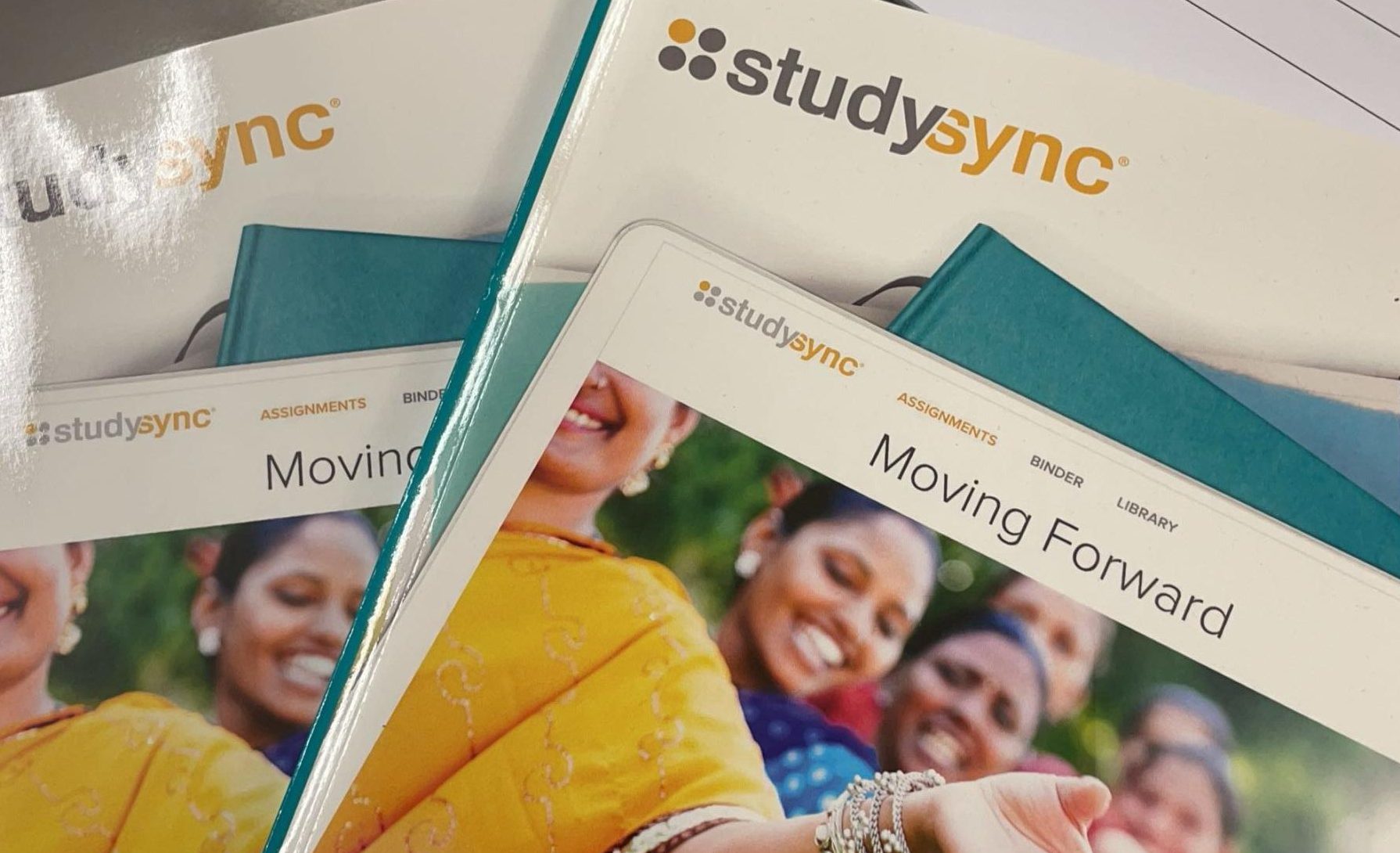

In English classes, it seems like technology is negatively affecting students.

According to The Atlantic, there has been an increase in students who struggle to understand books in high-level classes.

Nicholas Dames, a teacher referenced in the article, has required reading in his college classes which often includes very long and dense books that must be completed within a week or two. A struggling student “told Dames that, at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.”

The article further explains that students can no longer tolerate reading a stanza of Shakespeare and stare blankly at the pages of “Pride and Prejudice.” It’s not just the old language structure that stumps them, “they struggle to attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot.”

This isn’t just happening in college, Advanced Placement (AP) Literature and Composition teacher, Andrew Kurnas, confirmed he has noticed the change occurring within our school.

“There is a noticeable difference from before COVID to now,” he pointed out. “Not in everyone, but in a lot of students. The difference is reading stamina. They aren’t reading as much or as often and as late into life on their own.”

Kurnas added, “I think they aren’t teaching people to read as children and I think it has to do with computers and social media. It’s connected to how they take the enjoyment out of what we have from longer, more sustained literature. It hasn’t happened to everyone, but it has to a lot of people.”

There is some truth to this. A study by the National Literacy Trust (NLT) shows that only 34.6 percent of eight- to 18-year-olds enjoy reading in their spare time.

According to The Guardian, “This is the lowest level recorded by the charity since it began surveying children about their reading habits 19 years ago, representing an 8.8 percentage point drop since last year.”

This has been a concern since 2016 when 2 out of 3 children claimed to enjoy reading.

Why are these programs being used?

This phenomenon may be linked to online programs and teaching requirements that are only meant to prepare students for state testing.

As schools implemented online requirements that switch out full-length novels, poems, epics, and plays for excerpts a sense of tradition is taken out of the classroom.

Think about your elementary school years: sitting with your class with hot chocolate in your hands, reading “The Polar Express” before winter break, or waiting to get that call for a snow day, and working hands-on in most of your classes. It’s all been replaced with virtual learning days. Thanks to technology, traditional snow days are no more.

Kids no longer act out Shakespeare, discuss topics in a large group, and connect through discussions about literature. It’s been replaced by inhuman online programs. How are students meant to understand literature, something that embodies the human experience, through a machine? It’s not fun for the students or teachers.

“I don’t like learning literature online because I don’t feel like I’m learning anything and it is very boring,” expressed Grace Gao, ’27. “I feel that StudySync (an online learning tool required by the Stroudsburg districts) is draining and teachers shouldn’t give students four StudySync assignments in one week.”

That isn’t to say there aren’t students that enjoy online learning. Amari Lewis, ’26, explained, “I like them because they’re easy to use. I think with books we have more chances to practice pronunciation for words, but we don’t strictly use online programs so it’s okay.”

Forbes explains that it’s important for kids to “delve into the full context, not just some key quotes….time to dig in and reflect on the ideas contained in the text.” They have to know how to “discuss with fellow readers, sharing and exploring ideas, examining different perspectives and interpretations. Maybe even take a pair of works and really think about how they connect.”

There may simply be a lack of balance between online and physical learning. Still, there are mixed feelings about technology in classrooms.

“I go back and forth between consistent use and understanding it, but I fear the ultimate outcome and only path forward for actual learning of the quality we used to have would require stopping the use of a lot of this technology,” admitted Kurnas.

What does state testing being online mean?

In recent years state testing, including the Keystones and SATs, have switched from paper to computers.

New in 2024-2025, AP literature exams are strictly online.

A study conducted by The Mountaineer shows that out of 88 students 51 percent preferred paper testing, 30 percent preferred online testing, and nineteen percent had no preference.

Though online testing often gives students their results faster, it can make the tests harder for some students to take said tests. A study held by ScienceDirect showed that “students who took such tests online lagged behind their peers who took paper tests, performing as if they’d lost several months of academic learning,” as explained by Edutopia. The same study showed that low-income students, non-native English speakers, and students with disabilities all scored lower on these online tests.

For example, computer screens negatively affect people with dyslexia. The glare of a computer with bright white backgrounds can worsen a person’s symptoms and result in the need for accommodations such as color changes.

Aside from this, studies have shown that staring at screens for a long period can result in migraines. MedicalNewsToday explained that people who spend hours staring at computers, phones, TVs, etc, may face an “increase in headaches and migraine, which both consist of a throbbing, constant, sharp, or dull pain in the head that can make it difficult to carry on with daily tasks.”

If students spend hours looking at computers in school (twenty minutes writing a paper, completing a digital test, watching an EdPuzzle, etc.) it makes sense that students face painful headaches.

Now imagine taking online state testing, with the average test lasting just over three hours. It seems like a disadvantage to students to administer them online. Wouldn’t success and focus be more difficult with a killer migraine?

Since COVID-19, state test scores have fallen behind. HeyTutor explained that in core subjects (math, English, and science) ” from 2018 to 2022, students’ scores fell by a record 15 points in math, and reading fell by twice the prior record, or by 10 points.”

This is shocking since before 2018 scores didn’t drop more than five points.

This study found that from “2012 to 2022, nearly half (46%) of the participating nations had declining scores in two out of the three subjects.” The decline in scores can’t be connected to COVID-19 since “reading and science scores peaked between 2009 and 2012 and started declining years before the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Though online learning has been around since the late 80s, it gained popularity and gradually changed education, but schools became dependent on online schooling in 2020.

So maybe it’s time to ditch the required online programs and stop only focusing on state testing. Let’s bring some life back to the classroom and away from screens.