Indigenous people of PA

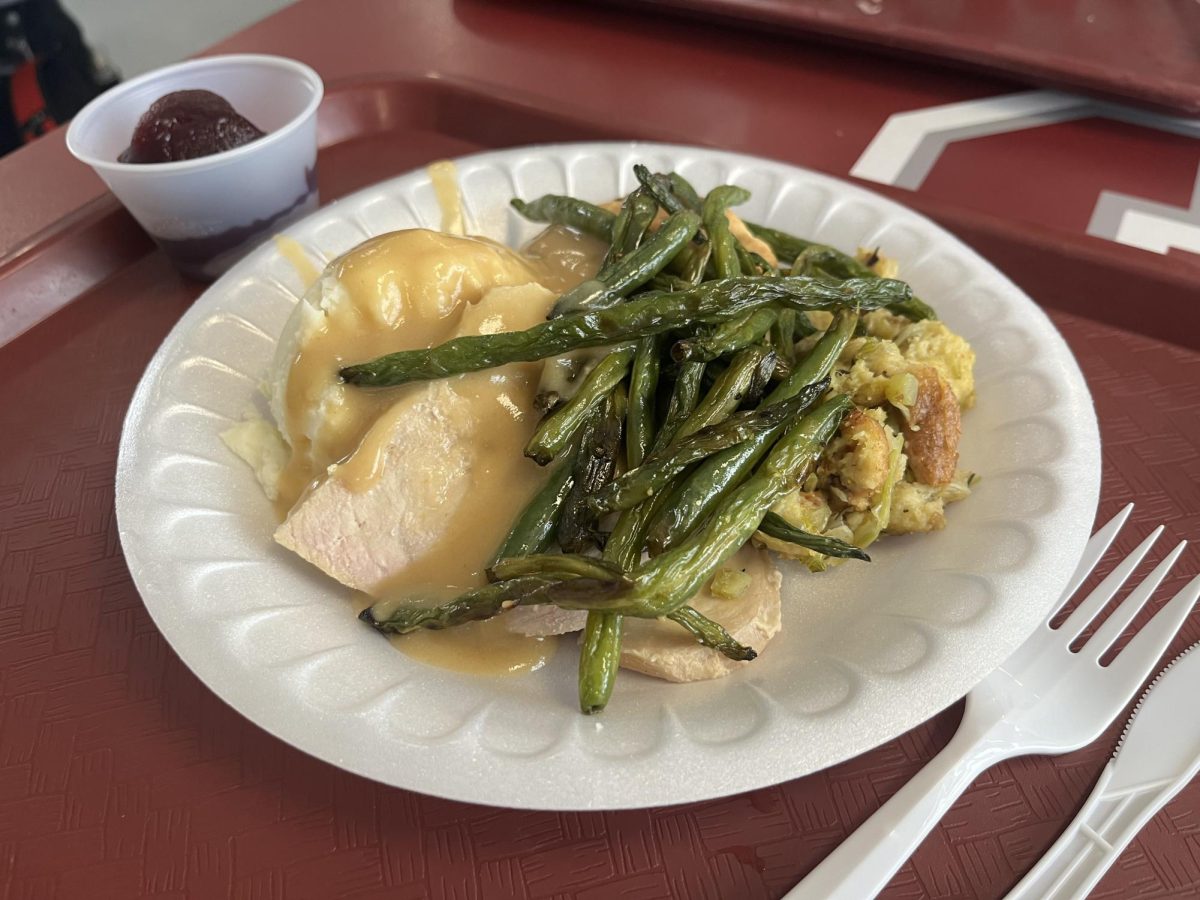

Thanksgiving is on the way so as you slice into turkey and dig into a loaded plate consider: Do you know the real origins of Thanksgiving?

The truth is: it’s not all hand turkeys and rainbows.

The holiday is haunted by shades of red with colonization, diseases spreading, and cultures wiped out. It wasn’t a group of strangers meeting over a meal, cheering for new friendships found.

Pennsylvania has had a huge native community from over 16000 years ago to 1680, according to Millersville University.

The Pocono Mountains even says the Stroudsburg area is one of the oldest Native American sites in the Northeastern United States due to archaeological evidence dating back over 10,000 years.

Pennsylvania was home to six indigenous tribes: the Iroquois, Lenape Delaware, Munsee Delaware, Erie, Shawnee, and Susquehannock.

Keep reading to learn the truth about Thanksgiving and the people affected during the holiday’s creation.

Most of the “First Thanksgiving” story is a myth. According to the National Archives, the story of the first Thanksgiving story was created decades after the first celebration.

According to Ap Government teacher, Anthony Lanfrank, “The idea of Thanksgiving is not a wholly American holiday. There have been Thanksgiving feasts recorded in history by the French and Spanish before colonies set up here. It was religiously followed by a big feast.”

The truth is residents of the Mayflower, pilgrims, landed on Wampanoag land, but weren’t the first Europeans the natives had come into contact with. By then the Wampanoag had already learned some English and warily formed an alliance with the pilgrims because it was the strategic thing to do.

The Wampanoag taught the pilgrims about hunting and farming, making the first Thanksgiving possible.

In 1621, 90 Wampanoag joined 52 pilgrims in what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts where they celebrated a successful harvest.

Lanfrank explains, “The way it’s taught here isn’t entirely historically accurate. Did pilgrims in the north eat a feast with Native Americans….yes, but the feast originally was just for the pilgrims. The Native Americans were invited because they heard gunshots and came to the aid of the Pilgrims (protective alliance). The shots were celebratory by the pilgrims. So the Native Americans were then invited.”

This peace was short-lived and within one generation, war broke out resulting in the Wampanoag losing not only their independence but much of their territory.

The Citizen Potawatomi Nation expands upon some details including the Pilgrims awful hygiene and how it brought sicknesses to the Natives.

Before the pilgrims came to America English and French fishermen spread despises when they came looking for new fish and to capture Native Americans for slavery. It’s said that “within three years the plague wiped out between 90 to 96 percent of the inhabitants of coastal New England. Native societies were devastated.”

The story of Squanto, the Indigenous man who taught the English to farm, is watered down.

Six years before the pilgrims came slave-traders captured him and brought him to England. He learned to speak English and eventually escaped, returning home to North America in 1619.

In his time away from home European plagues spread across Patuset, his village and he returned to his village being extinct. He was the sole survivor.

He was later taken as a prisoner by the Wampanoag and used as a translator for the tribe to communicate with the Englishmen.

“Squanto’s travels acquainted him with more of the world than any Pilgrim encountered,” expressed James W. Lowen according to Citizen Potawatomi Nation. “He had crossed the Atlantic perhaps six times, twice as an English captive, and had lived in Maine, Newfoundland, Spain, and England, as well as Massachusetts. All this brings us to Thanksgiving.”

While many Americans can peacefully celebrate Thanksgiving many Indigenous people see it as a painful reminder of the eradication of their home, culture, and people.

“It’s important for students to learn the history of what happened to Native Americans and other minority groups in history class as they grow older,” expressed Lanfrank.

Understands the past, be grateful in the present, and work toward a better future.

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) people were some of the most influential in Native American history.

Iroquois called themselves “Haudenosaunee” or “the people of the longhouse.” The name Iroquois means “rattlesnake” and comes from the Algonquins, their rival, due to their skills in hunting.

They lived in Ontario, upstate New York, and some sections of Pennsylvania, as explained by Native Hope. They were an established group who settled near hills and lakes because they were easy to defend.

They weren’t nomadic, but the Iroquois people moved every ten years to protect the wildlife of the areas inhabited. By living on the northern shores of Lake Ontario the Iroquois people were able to gain control of fur trade among the north and west.

“Iroquois” refers to five tribes who make up the “Iroquois Confederacy: the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca who

The confederacy started in the 1500s after fighting within the tribes. It was “championed by the Great Peacemaker (Deganawidah), Hiawatha, and Jigonsaseh,” as stated by Native Hope, and was “a political system with a two-house legislature.”

Representatives within the house were called “sachems,” and contained adversity council members called “Pine Trees.” The council had 50 men, and delegates, all chosen by the clan mother. Pine Trees could be anyone who earned their spots through heroic endeavors.

The groups settled disputes through representatives and an organized system of kinship, and loyalty.

According to Native Hope, the Iroquois Confederation was so advanced “Benjamin Franklin greatly admired their form of council, and aspects of the confederation can be seen in the United States Constitution.”

The Tuscarora people joined the group in 1722 and renamed the Confederacy “Six Nations.” It disbanded during the Seven Years’ War when the Confederacy took different sides and split up.

Their religion included a belief of spirits, that all plants and animals had spirits as well, and held great value in dreams.

The tribe held six religious ceremonies a year: a New Year Festival held in midwinter, A Maple Dance held in February, the Planting Festival, the Strawberry Festival, the Green Corn Festival, and the Harvest Festival. They also participated in healing ceremonies.

Women were held in honorable roles within their society, believing to be connected to the earth’s power to create life. Because of this, they were in charge of food distribution, and family lineage was traced through the mother’s bloodline.

The Erie (Cat or Long Tail) are an extinct tribe with their only lineage being tracked in other Iroquoian lineages, according to Millersville University. As a result, the Erie people are somewhat of a mystery.

They resided south of Lake Erie in the 1600s. It’s said no known Europeans visited their village and there is no recorded language of the Erie people.

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, scholars speculate that they were “Iroquois, based on similarities between them and other Iroquoian-speaking peoples.”

Tribe information was gained through archaeological records and secondhand French sources.

The Erie were an alliance of several tribes, each of which had their own towns. These villages were heavily populated and “extended from present-day Buffalo, New York, south to Toledo, Ohio, and east to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” Two of those villages were the Rigue and Gentaienton (Riquehronnons and the Gentaguehronons).

They blocked access to hunting grounds in the Ohio Valley, causing a war between the Erie and the Iroquois in the 1650s. The Iroquois defeated Erie in 1654-1656. The Erie ran, but many were captured by the Iroquois.

It is through the mixing of the tribes after this war that the Erie were lost to time.

The AVON Historical Society shares how they were sedentary farmers of the Eastern Woodlands area who showed southeastern cultural traits, like the use of poisoned arrows and the building of palisaded villages.

Erie people lived in traditional long houses that could hold several families. They farmed corn, beans, and squash during harvest season and partook in the winter hunt.

Though the Europeans could not get in contact with the Erie, the tribe did communicate with other tribes. They traded with the Susquehannock, though they were not allowed to get European goods from them such as firearms.

The Lenape Delaware is also known as the Lenni Lenape (People of the Stony Country) tribe.

They lived along the Delaware River and, according to the Delaware Tribe, were one of the first tribes to come in contact with Europeans in the early 1600s.

Among other tribes, they were called “Grandfathers” because they were “respected by other tribes as peacemakers since (they) often served to settle disputes among rival tribes.” They often took the path of peace, but were fierce warriors.

The Lenni Lenape were nomadic and spoke the Alginquain language family, as stated by West Philadelphia Collaborative History.

They were divided into three subtribes: the Minsis (Munsee, People of the Stone Country) who inhabited northern PA, the Unami (People Who Live Down-River) who lived in the central regions of PA, and the Unalachtigo (People Who Live by the Ocean) who inhabited south PA.

Munsee can also be considered their own tribe because of distinct differences in culture.

Residing in groups along rivers and creeks and , because of their constant farming, they had to relocate every two decades.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Lenape resided in Pennsylvania centuries before Europeans arrived. Excavations in West Philadelphia revealed they date back at least 6000 years ago. The land inhabited by Lenape later became Philadelphia.

The Lenape Delaware tribe lost all their land in the “Walking Purchase” deed of 1737. The Pennsylvania Conservation Heritage Project explains the purchase as a race. The natives set out to measure out land claimed to be bought by Thomas Penn. They explain how the document “stated that the amount of land would be measured by a day and a half’s walk from an agreed upon starting point. The Lenape questioned the validity of the document, yet, in the end, they had no choice but to participate.”

The “walk” was more like a race with three well-trained Europeans who were assisted by settlers. By the end of the race, “1.2 million acres were taken from the Lenape and given to the Penn family.”

The Lenape went to the Iroquois for help but were left abandoned. Those who stayed were forced to settle on unhealthy land or work for the colonists. Most made the decision to move west along the Susquehanna, Allegheny, or Ohio rivers.

Today, most of the Lenape communities are found in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Wisconsin, Ontario, and New Jersey. In 1982, New Jersey officially recognized the Lenni_Lenape tribe in its hometown of Bridgeton called “Indian Town,” as stated by West Philadelphia Collaborative History.

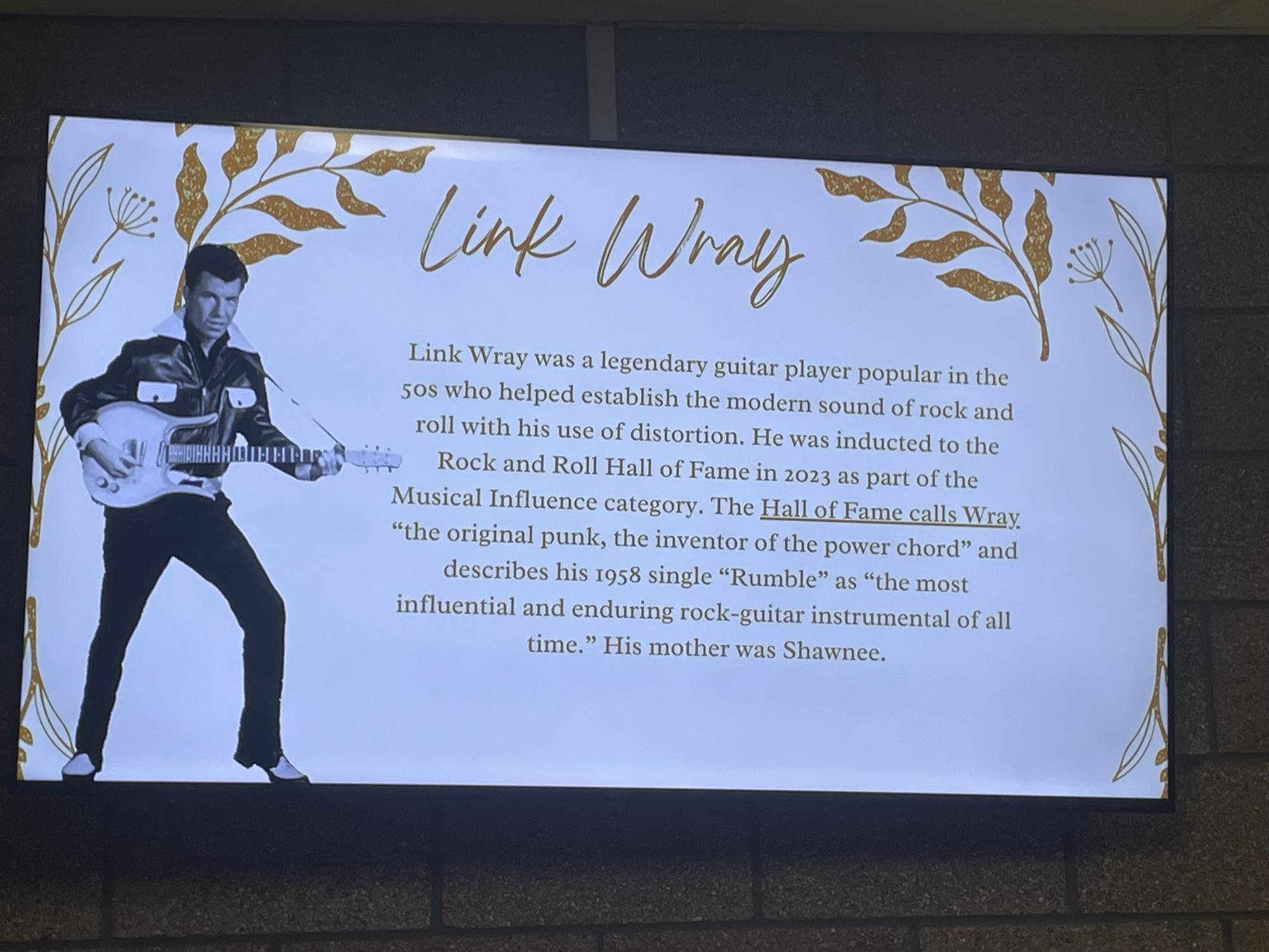

The Shawnee occupied southern Ohio, West Virginia, and Western Pennsylvania, according to Dartmouth Libraries.

“Shawnee” comes from the Algonquian word “Shawun” or “southerner” which refers to their original location in the Ohio Valley, south of other Great Lake tribes. This is why they are also known as the “Ohio Valley tribe.”

The history of the Shawnee is full of displacement, wandering, and rebellion. The Iroquois chased them out of their home in the 1600s because of land disputes. Shawnee people were forced to disperse and by 1730, most returned to their home in the Ohio Valley.

In 1761 when the Senecas called for an uprising against the British, the Shawnee were one of the only two tribes to respond. The ruse was stopped by Sir William Johnson. Another uprising was planned in 1763 and the Shawnees joined the Ottawa Chief Pontiac but were stopped by Lord Jeffrey Amherst.

The Shawne participated in the Congress of Fort Stanwix in 1768 and in the summer of 1774. It was there the tribe fought with Virginians leading to Lord Dunmore’s War. They insisted they fight, but were severely outnumbered. Their chief Cornstalk signed a treaty that gave up the Shawnee’s claims over the southern part of the Ohio River.

The tribe was then split in two with some migrating to Missouri (the Absentee Shawnee) while others settled in eastern Oklahoma (the Loyal Sawnee) where they relocated to reservations in Kansas.

Tecumseh and his brother (the Shawnee Prophet) led another failed uprising against American settlers in the border wars of the Ohio Valley at the turn of the 19th century. They founded the pan-Indian Prophetstown settlement in 1808 and fought on the side of the British in the War of 1812.

When Kansas became a state the non-native citizens demanded the removal of all the indigenous people and, in 1869, the Loyal Shaene moved to land the Cherokees offered them in Oklahoma. Some decided to stay in Kansas on reservations.

During the 1980s the Shawnees fought to gain separate tribal status and became a recognized tribe in 2000.

They had many ceremonies including “the spring Bread Dance, held when the fields were planted; the Green Corn Dance, marking the ripening of crops; and the autumn Bread Dance.”

The Shawnee was composed of 5 major divisions, each organized through patrilineal (religious statute through the father’s bloodline) clans.

Their Chief was generally hereditary while war chiefs were selected through acts of bravery, skill, and experience.

The Susquehannock are an extinct tribe with most members being wiped out due to disease and massacres, as explained by Millersville University.

According to SRBC, the Susquehannock could be found “along the Susquehanna River in New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland.” They moved frequently to find land as farmers and followed the fur trade along the river and Chesapeake Bay.

The Shenks Ferry people had occupied the region for over 500 years and were absorbed into the Susquehannock culture. It is unknown if the union was a product of war, violence, or an agreed-upon treaty.

The Susquehannock moved south to gain better control of the fur trade, but were quickly trapped outside of Susquehanna Valley, becoming a ‘“middle-man” for furs from Native groups in the areas of New York, Ohio, and Canada.”

Susquehannock people had conflict with the Seneca tribe from New York and had constant fights with them. Overcome by disease, the camp lost hundreds of members with about 500 survivors fleeing to the Potomac River in 1675. When this failed they moved back to the Lower Susquehanna Valley, with the permission of the Seneca and stayed in land provided by William Penn.

The Susquehannock later became known as the Conestoga Indians and lived in peace through the French and Indian War.

In 1763 they were attacked two weeks before Christmas by a group of vigilantes from Harrisburg. As explained by SRBC, these people were known as the “Paxtang Boys,” and were upset by the “Indian incursions of Pontiac’s Rebellion.”

Survivors were placed in the Lancaster jail for this town’s protection, but after two days the Boys returned and slaughtered everyone in what was known as “the most horrible massacre that was ever heard of in this, or perhaps another province.”