Are monsters born or made?

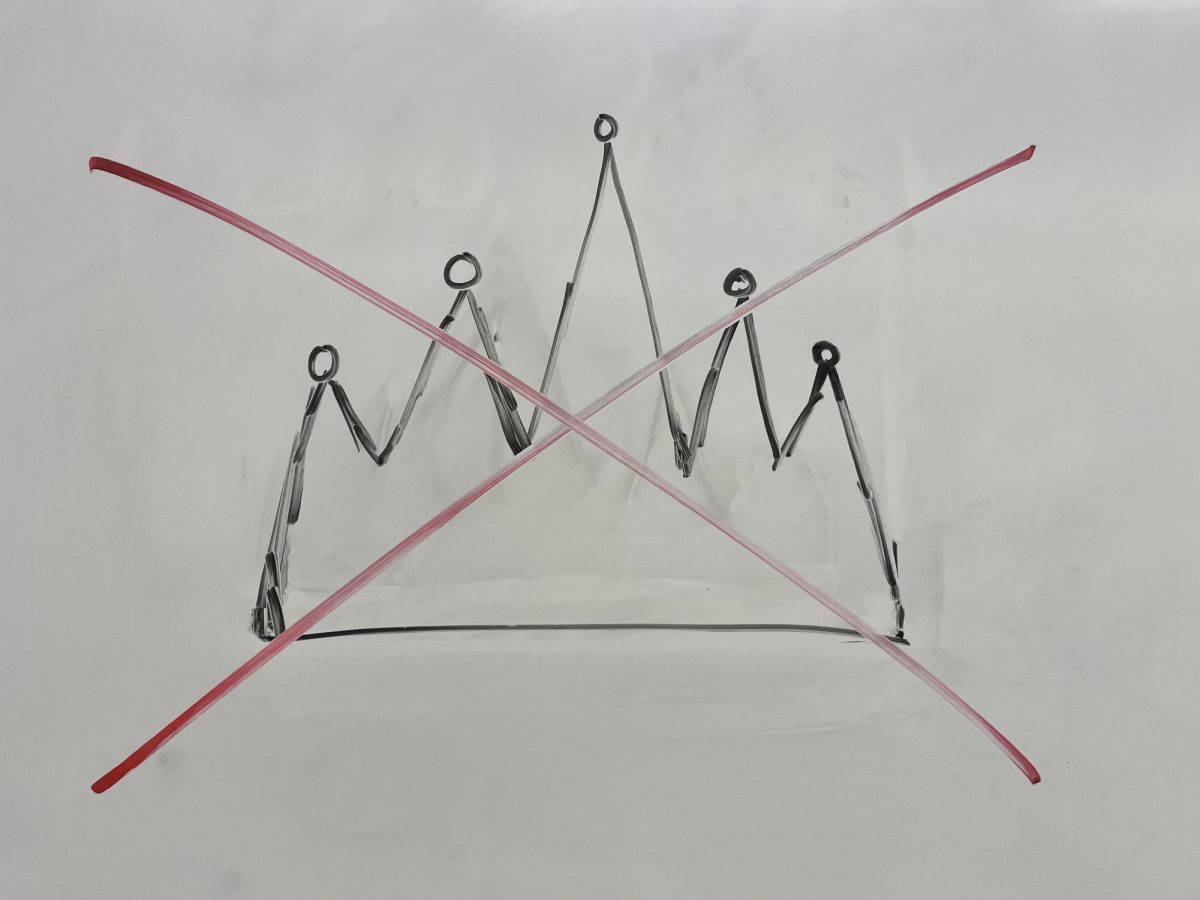

When people think of Medusa, the gorgon with snake hair and eyes that turn people to stone, there are typically two interpretations that come to mind: a symbol of survival or a grotesque beast.

Today, Medusa is often used as a symbol for survivors of sexual assault. But how did the myth change over time and how is it depicted in Natalie Haynes’ novel “Stone Blind”?

How has the myth of Medusa changed over time?

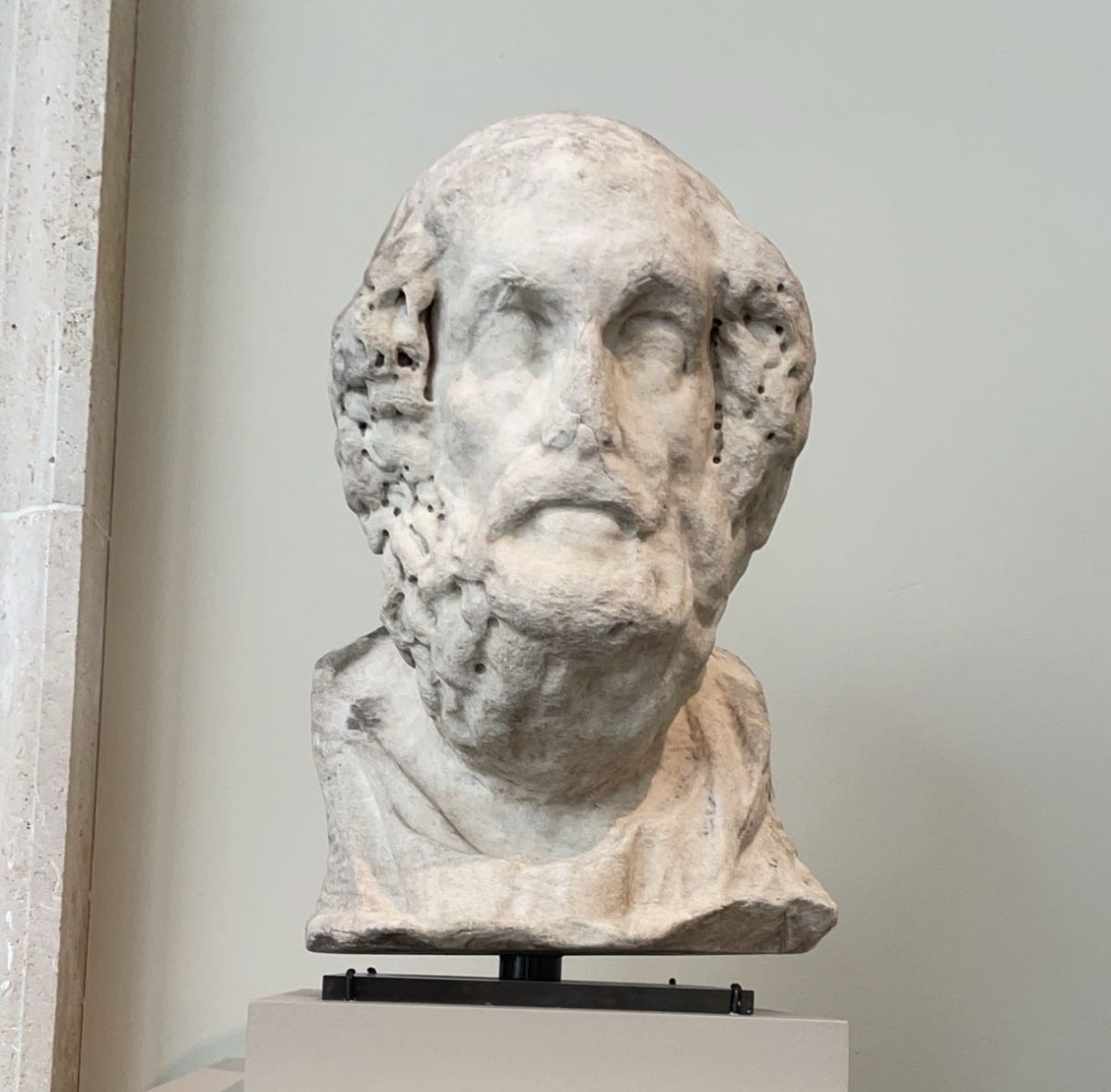

The original myth of Medusa came from the Greek poet Hesiod who wrote it in the 8-7 centuries B.C.E. How Stuff Works explains how in the original myth Medusa was born a gorgon and had two sisters. Unlike the other gorgons Medusa “was mortal while her sisters Sthenno and Euryale were ageless and lived forever.”

A century after Hesiod the Greek poet Stasinus added that she lived in “Sarpedon, a rocky island in deep-eddying Oceanus.” In the 5th century B.C.E. the Greek playwright Aeschylus added her horrific appearance to the story. He described gorgons as “three winged sisters, the snake-haired Gorgons, loathed of mankind, whom no one of the mortal kind shall look upon and still draw breath.”

These depictions of Medusa don’t follow the victim plot that’s well known today. She’s just a monster whose greatest tragedy was being killed while her sisters can live forever.

It was Ovid, a Roman poet, who completely altered Medusa’s story in his “Metamorphoses” (c. 8 CE). According to Athenagaia, in Ovid’s version, Medusa was a beautiful priestess of Minerva (Athena) with beautiful hair that caught the eyes of Neptune (Poseidon). Neptune assaults Medusa in Minerva’s temple and instead of punishing Neptune, Minerva turns Medusa into an ugly snake-haired monster who turns people to stone. Later on, Minerva helps the hero Perseus murder Medusa.

Ovid’s depiction of Medusa was a political statement where “ the gods can be seen as a metaphor for the way that Ovid perceived those in power,” as explained by Study.com. Medusa’s story is a commentary on how women are often blamed for their assault, something that results in questions like “What was she wearing?” and other ideologies that put blame on the victim.

“I think that the actual story kind of gets lost through ‘Percy Jackson’ and other interpretations of it,” commented Rebecca Dishong, ’25, “I think it’s important for people to realize good and evil isn’t black and white. You need to look a the gray because good people do bad things sometimes.”

Over time, people have interpreted the myth in many different ways. Some people believe the curse Minerva placed on Medusa was a gift to protect her similar to how in some myths Minerva turned Arachne into a spider to save her life after an attempted suicide.

Medusa wasn’t a villain to the ancient Greeks because they understood good and evil were not simple.

“In Greek culture, the world was composed of complementary dualities — day and night, Mount Olympus and Hades — and both good and evil could exist at the same time, even within the gods,” explains How Stuff Works.

“Stone Blind” by Natalie Haynes Book Review

Haynes mixes all these versions of Medusa into a novel that changes the perspective from monster to victim.

It tells the story of Medusa from her birth to after her death. Born a gorgon with wings and serpents for hair, Medusa was a mortal raised by her immortal siblings Sthenno and Euryale. It follows as Ovid’s story did, she is assaulted by Poseiden, cursed by Athena, and killed by Perseus.

However, the story isn’t just about Medusa. Haynes shifts points of view and tells the story of Athena, Perseus, Hera, and many other figures as they coincide with Medusa’s story.

“The swapping of narrative viewpoints and lack of linear plot can be jarring at first, but Haynes’ sense of humor does a lot to smooth over lag in the narrative and refocus the reader,” commented Annmarie Patterson in her review of the novel in The Paideiain Institute.

Patterson comments on Haynes’ background as a stand-up comedian and expresses how the humor played a part in the setup of the novel, adding comfort to otherwise tense scenes. The gods’ family dynamic is comedic and Athena’s “relationship with Perseus bears more resemblance to that of a newly hired employee learning how to deal with their incompetent boss than a hero called to action by a goddess.”

These shifting points of view provide interesting side stories, but leave the focus on Medusa lacking.

“The problem I keep coming back to is that it’s just not got enough Medusa,” points out Motherbookerblog, “I wanted more of her perspective. I wanted her to have more agency. That was supposedly what the book was about. Instead, we get to spend a lot of time in the presence of the same Gods and heroes we read about.”

It leaves Medusa feeling like a side character in a story that’s meant to be about her. She doesn’t feel as fleshed out as other characters in the novel.

“Haynes hit upon something I have noticed in the Greek myths for a while now; there are more power dynamics at play than only those produced by gender inequality,” expressed Patterson, “Women can exploit these. Women are capable and powerful, but not all of us are always good. We’re human, dealing with a human complexity that is both good and bad.”

The characterization of Athena feels fleshed out and memorable. A goddess unable to feel empathy for humans who use the power she has to manipulate the situation she’s in makes sense. Medusa’s character doesn’t feel nearly as memorable.

The story plays into the theme of what makes a monster and pushes the narrative that Perseus is the monster in this novel. While he is perceived as a coward throughout the novel, the characters breaking the fourth wall to question whether or not the reader believes Perseus is still a hero can be annoying and leave the novel feeling insecure. If Perseus is a well-written antagonist, the reader should be able to come to this conclusion without having to be told what to think.

It feels almost unfair to frame Perseus as a villain to make Medusa’s story sympathetic. As far as heroes go, Perseus is one of the few morally justified ones and Medusa should receive sympathy with or without him as a villain.

Perseus does not kill Medusa because he wants glory and sees her as ugly like “Stone Blind” implies.

Medium explains the story of Perseus following a prince who was prophesied to kill his grandfather. As a result, his grandfather attempts to kill Perseus and his mother, Danaë. They’re thrown into a box to drown, but wash up on the shores of a far-off island and are adopted by a fisherman.

When Perseus is older the king of that island, Polydectes, tries to force Danaë to marry him. Perseus wants to stop this and is sent to get Medusa’s head, a task that’s meant to be impossible, in exchange for his mother’s freedom. He kills Medusa not because of her appearance, but to stop his mother from being assaulted.

“Using Perseus as the symbol of patriarchy completely ignores the reason why he’s there and his own relationships to women through his story,” points out Medium. He saves and marries the princess Andromeda because he “happens to be in the right place at the right time,” and is loyal to her after they marry, a feat most Greek heroes struggle with.

The murder of his grandfather is an accident which Perseus feels awful for. His grandfather just so happens to get hit by a poorly aimed discus at an athletic competition and Perseus “abdicates rulership of his grandfather’s thrown out of shame for having killed him.”

Perseus’ own story is just as compelling and driven by the same horrors in Medusa’s. Isn’t the tale of Medusa being killed by a desperate boy trying to save his mom from the fate Medusa endured more compelling and tragic than it being an act of aggression?

“Perseus shouldn’t be villainized. There’s no reason to do that to him, he’s fighting for this mom. There’s no ill intent towards Medusa, he’s just trying to preserve his mothers well being,”expressed Leah Robertson, ’25. “While Medusa didn’t deserve what happened to her, Perseus still isn’t in the wrong. It would be more helpful to people if Medusa was dead anyway.”

In “Stone Blind,” Medusa feels defined by men who have controlled her narrative for hundreds of years in a story that is meant to show her as someone more.

Despite this, there is still a very clear feminist undertone to the book.

“‘Stone Blind’ is about perspective and point of view,” points out Motherbookerblog, “It turns the table on some of the more heroic moments in Greek mythology…The main difference between what makes a monster and a hero is who is telling the story. Medusa, as Perseus sees her, is only a monster because she isn’t beautiful. She’s done nothing to hurt anyone and is just trying to deal with what happened to her. A girl who loves her sisters and sees their beauty when others only fear them.”

The book has its ups and downs, but it doesn’t accomplish what it set out to do. It may be appealing to those who go in blind without any previous knowledge on Greek/Roman mythology, but if what you’re looking for is a story that makes a statement on people in power with sympathy for Medusa, it’s best to go back to the source material and read Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.”